Two-sentence letter from federal official did not exonerate Tshibaka

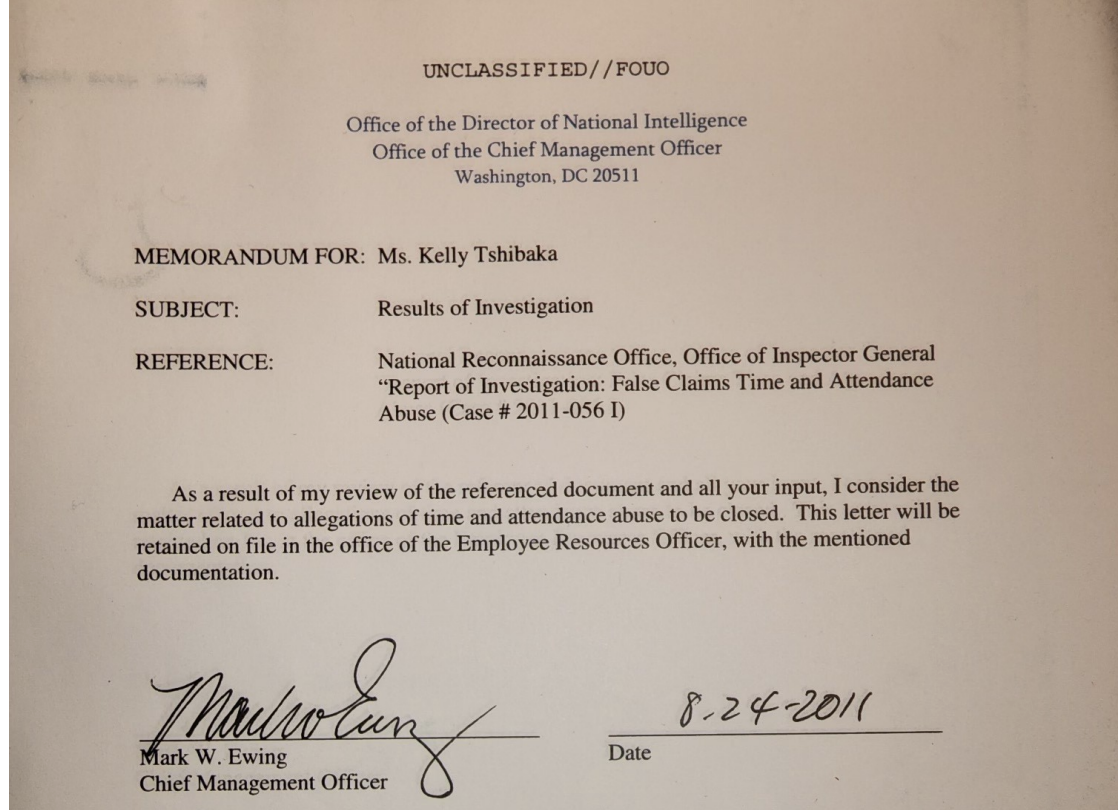

Kelly Tshibaka released to the Anchorage Daily News a copy of the two-sentence letter that she says exonerated her of all claims made against her in an investigation by the National Reconnaissance Office in 2011.

The letter does not exonerate her. The letter says the matter is closed, which is not the same thing.

Some background on this matter. Tshibaka worked at the time for the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

Fellow employees complained that she was getting paid for hours she was not working.

Tshibaka has claimed that the investigation was retaliation by fellow employees and by federal officials opposed to her attempts to fight waste, fraud and abuse.

After a preliminary investigation, to avoid a conflict of interest, the ODNI inspector general transferred the entire matter to another agency—the National Reconnaissance Office—and asked its inspector general to take charge.

The National Reconnaissance Office investigators came back with this report alleging that between 2008 and 2011 Tshibaka falsified her federal work records and claimed that she worked 596 hours that she should not have been paid for.

The disputed hours included comp time claims, unexplained absences during the day, inappropriately charging hours to excused absences when she was already on leave and when there was an early dismissal for federal holidays. At her pay grade, the hours cost the government $36,000.

The NRO is one of five major intelligence agencies, dealing mainly with reconnaissance satellites. The agency sent the report back to ODNI for possible action after the Justice Department declined to prosecute Tshibaka.

On the list of people the NRO directed the investigation to, the person at the top of the list Mark Ewing, the chief management officer of ODNI.

Ewing wrote that he reviewed the NRO investigation and listened to what Tshibaka said about it. He did not write that he or anyone at ODNI performed a separate investigation or discovered that anything in the NRO report was erroneous.

We don’t know how much of this is an inter-agency dispute in which one inspector general’s office found reason to criticize another. Or whether the NRO criticism of some of Tshibaka’s supervisors played a role in how it was handled. We also don’t know if Ewing’s two-sentence letter was a means of making the issue go away.

The NRO investigation did not put some of Tshibaka’s superiors in the best light, mentioning specifics in which officials said they did not know about what she was charging as comp time.

Tshibaka was transferred to a cubicle down the hall in September 2011 in the same agency. At the time she told friends and wrote on her blog that her new job was one she really wanted.

But in a 2014 sermon, Tshibaka contradicted that claim. She said she wasn’t happy, having been moved to a cubicle down the hall. She said that God had told her she would be given a position with broader responsibilities.

“I found a quiet place at work where I could hide where I screamed out to God almost every day at work, ‘This is not broad. I don’t understand. Are you messing with me?”

She said she waited for two years when an old boss of hers called about a job that could put her back on the track that the investigation had knocked her off of. Six weeks later, in July 2013, she had a new job with the inspector general’s office of the Federal Trade Commission, with broader responsibilities.

In late 2014, Tshibaka announced to her congregation that God had promised her she would be promoted, which she took to mean that she would become inspector general of the FTC.

She was one of two finalists for the position. The other finalist was Roslyn A. Mazer, a former boss of hers who Kelly had clashed with while working in the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

On Jan. 11, 2015, the Rev. Niki Tshibaka delivered a sermon in which he mentioned that Kelly did not get the job. He criticized the person who did.

“What was difficult was that the person got appointed to the position was a former boss of hers back when she was working in the intelligence community and this person is known to be a really bad manager. And she was a person that Kelly worked for years to try to get away from,” Niki said in his sermon.

“And so for her it wasn’t so much just the disappointment of not getting the job. It’s like ‘God, what are you doing? It’s like I’m being chased after by this lion. Like, this is not the person. Of all the people that you would have put over me, why are you putting this person over me when you know I prayed for years to get away from this person? And you helped me escape from under this person’s leadership.”

“So that’s been very difficult for her, trying to work through feeling unsafe,” Niki said.

The comment about God helping her “escape” from Roslyn Mazer’s leadership refers to Kelly Tshibaka’s experience in the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and the fraud investigation that clouded Tshibaka’s career.

Niki said he would not mention the name of the person hired to be the inspector general. He referred to her as “Jocelyn” and repeated that she was a bad manager who had been passed over for a number of jobs. He claimed the FTC had someone “missed” her track record and how “unhealthy and dysfunctional” it had been.

Mazer had far broader qualifications for the FTC job than Tshibaka. Mazer served in the position for three years.

Kelly Tshibaka remained at the Federal Trade Commission under Mazer until August 2015, when Tshibaka transferred to the U.S. Postal Service.