Permanent Fund's Russian holdings tank, leaving little to divest from

“The Permanent Fund’s biggest Russian stock holdings are in the state-owned gas company Gazprom, the private oil and gas company Lukoil, and the state bank, Sberbank,” the Anchorage Daily News reported Monday.

The newspaper told readers that the Alaska Permanent Fund Corp. and the Dunleavy administration do not plan to divest Russian assets. They want to keep investments out of politics. OK.

At the end of January the Russian holdings of the Alaska Permanent Fund were worth about $160 million. A week ago there was something to divest. Not so much any more.

The companies mentioned above have lost most of their value in the last month.

“Russian natural-gas giant Gazprom, oil-producer Lukoil and leading bank Sberbank are all penny stocks based on their trading on the London Stock Exchange, as the local market was shut for a third day,” MarketWatch reported Wednesday.

Gazprom, the largest Russia company, is down 75 percent. Lukoil has lost 86 percent of its value. The Russian bank Sberbank, down 99.9 percent since the start of the year, was trading at one point for one cent a share.

Russian stocks were not a major element in the Permanent Fund even before the meltdown, only 0.2%, so the collapse will have a small impact on the total fund.

Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, which is 15 times larger than Alaska's, faces the same problem. It also holds investments in Russia that are now worthless, mainly Gazprom, Sberbank and Lukoil. Norway will get rid of whatever remains, but it will take time, the fund said Thursday.

Norway’s fund managers met on the morning of the invasion and “decided to do very little,” Reuters reported.

While it may be too late to sell Russian stocks without huge losses, this is not just a matter of politics or the alleged Alaska interest in divorcing politics from business.

The Dunleavy administration wants to stop doing business with banks that oppose or question Arctic oil development, a recent example of mixing politics with investments.

There is also the question of economics and whether our investment managers should have acted in advance and unloaded Russian holdings when there was something to unload. Balancing and holding onto a long-term vision is made more difficult when parts of the world are collapsing.

The policy question about whether it is right to do business with Russia is made less relevant when the investments have already lost nearly all of their value.

The investment managers will say they are not market timers and that instant decisions, even in extreme circumstances, are unwise.

It’s a complicated matter, as is the question of whether divestment is warranted because Alaska should not do anything to benefit the Putin regime. Divesting when assets are next to worthless hurts the seller.

Divestment for political reasons first became a significant issue in the 1980s in Alaska during the debate about divesting from South Africa because of apartheid. Later, it was an issue regarding investments in Sudan in 2008.

In 2008, Gov. Sarah Palin and Mike Burns, then the head of the Permanent Fund, opposed efforts by Anchorage Reps. Bob Lynn and Les Gara to divest about $22 million from companies tied to Sudan.

"We've never done any social investing," Burns said. "It doesn't come free, and it's not good investment policy.”

In early 2009, the fund managers reversed themselves and said the fund would no longer invest in Sudan. But no bill passed the Legislature. In 2011, some lawmakers urged the fund to divest from Iran, another proposal resisted by the Permanent Fund.

Gara, now running for governor, supports divestment from Russia as does former Gov. Bill Walker, also a candidate. Gov. Mike Dunleavy hasn’t taken a position.

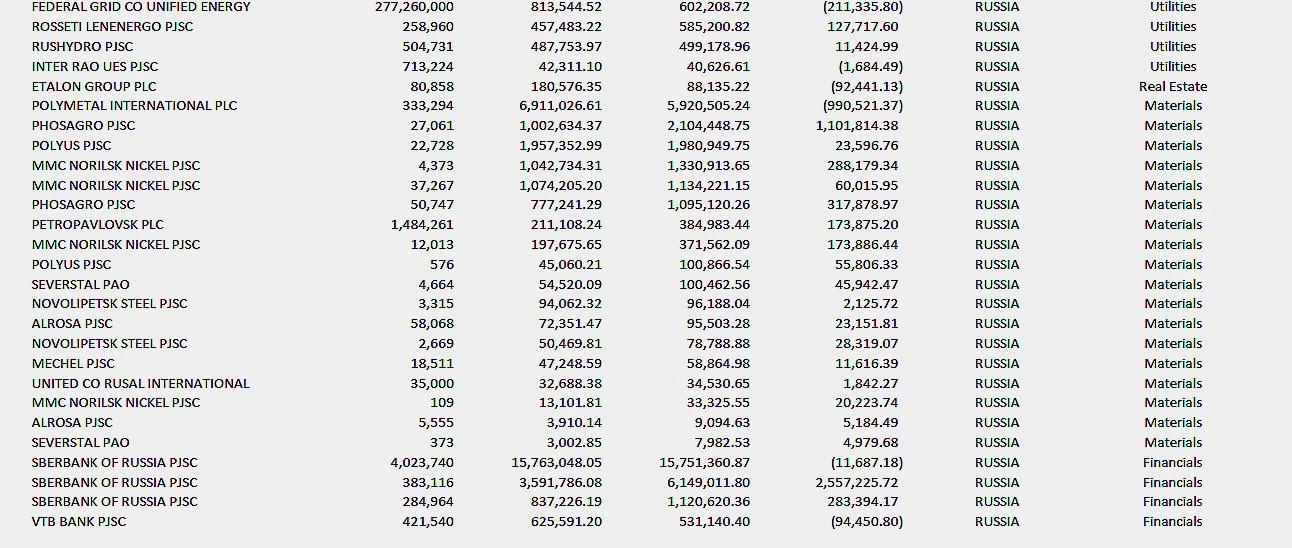

The charts below, taken from a Dec. 31 report of holdings by nation, show what the Permanent Fund had in Russian companies. Much of their value has evaporated.