Carl Benson and the secrets of ice fog

When it comes to a discussion of winter weather, the topic is never complete without recognizing the enduring contributions of the great Carl Benson, who ventured into the cold in the early 1960s in Fairbanks and began to unlock the secrets of ice fog.

Benson, 96, is still pursuing his scholarly studies, thanks to a good constitution and an unending sense of curiosity about the world around him. I can’t tell you how much I admire him.

“Ice fog is a special case for two reasons,” he wrote nearly 60 years ago. It is largely made by humans and it forms when injecting large amounts of warm water vapor into the atmosphere when the air is so cold it cannot handle it. The ice crystals become more numerous the longer the cold stagnant air remains.

He says now he made some errors in that study. The scientists who have followed his lead into the field, studying ice, snow and the atmosphere say his report remains both useful and informative.

Here is the full text of Carl’s 1965 study, “Ice Fog: Low Temperature Air Pollution.”

Benson’s report was based on observations taken during the winters of 1961-62 and 1962-63, when it was colder than it is today,

There were six ice fog periods in the 1961-62 winter, including a December day with a temperature of 62 below. For six days the highest air temperatures were colder than 50 below.

For 231 hours, the temperature was colder than 40 below. The second cold spell was from January 23 to January 29, 1962.

Ice fog “becomes a nuisance whenever temperatures go below minus 35 C (minus 31 F) in the Fairbanks-Fort Wainwright area of Interior Alaska,” he wrote.

At the time of his first ice fog research, there were about 30,000 people and 2,000 dogs in the Fairbanks area. There were about 17,000 vehicles in 1964. The number of cars that were used in the winter had grown sharply since 1948, when the headbolt heater appeared.

He wrote that while the exhaust from cars and trucks made up a small portion of the overall ice fog layer, it was a major source because the tail pipes were so close to the ground. “Also, they are probably the most dangerous of all sources because of products other than water which accompany them.”

Twenty-seven years ago, Ned Rozell went along with Benson to collect ice fog samples and wrote about the scientist for the weekly Geophysical Institute column, capturing some of Benson’s intellectual energy:

“At frigid temperatures, the air rids itself of ice fog in two ways, Benson said. When ice fog mixes with warmer air at the "lid" of the inversion, some of it converts to water vapor, which is invisible. Ice fog also falls out like rain, a phenomenon Benson took advantage of when he recently went out to gather some.

“To catch ice fog, Benson repeated a cold-snap ritual he has performed with other GI scientists since 1961. He placed several sheets of polyethylene-covered plywood at sites around Fairbanks. Ice fog precipitate, visible as a gray-brown layer on the snow, fell out of the air onto the plastic. Using a spatula, Benson shaved dirty frost off the rectangles of plywood. He collected the frost in a plastic water jug and sealed it. Later, he melted the residue into an unsavory broth of pollution particles and water. Besides water, ice fog contains carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and a slew of other chemicals wafted into the air by cars' inability to completely burn gasoline.

“During a cold snap, most people in Fairbanks yearn for the magic moment when the temperature warms to about minus 30, the point at which ice fog dissolves to become water vapor. Carl Benson is perhaps the only man in town who roots for long cold snaps--they give him more time to collect samples.”

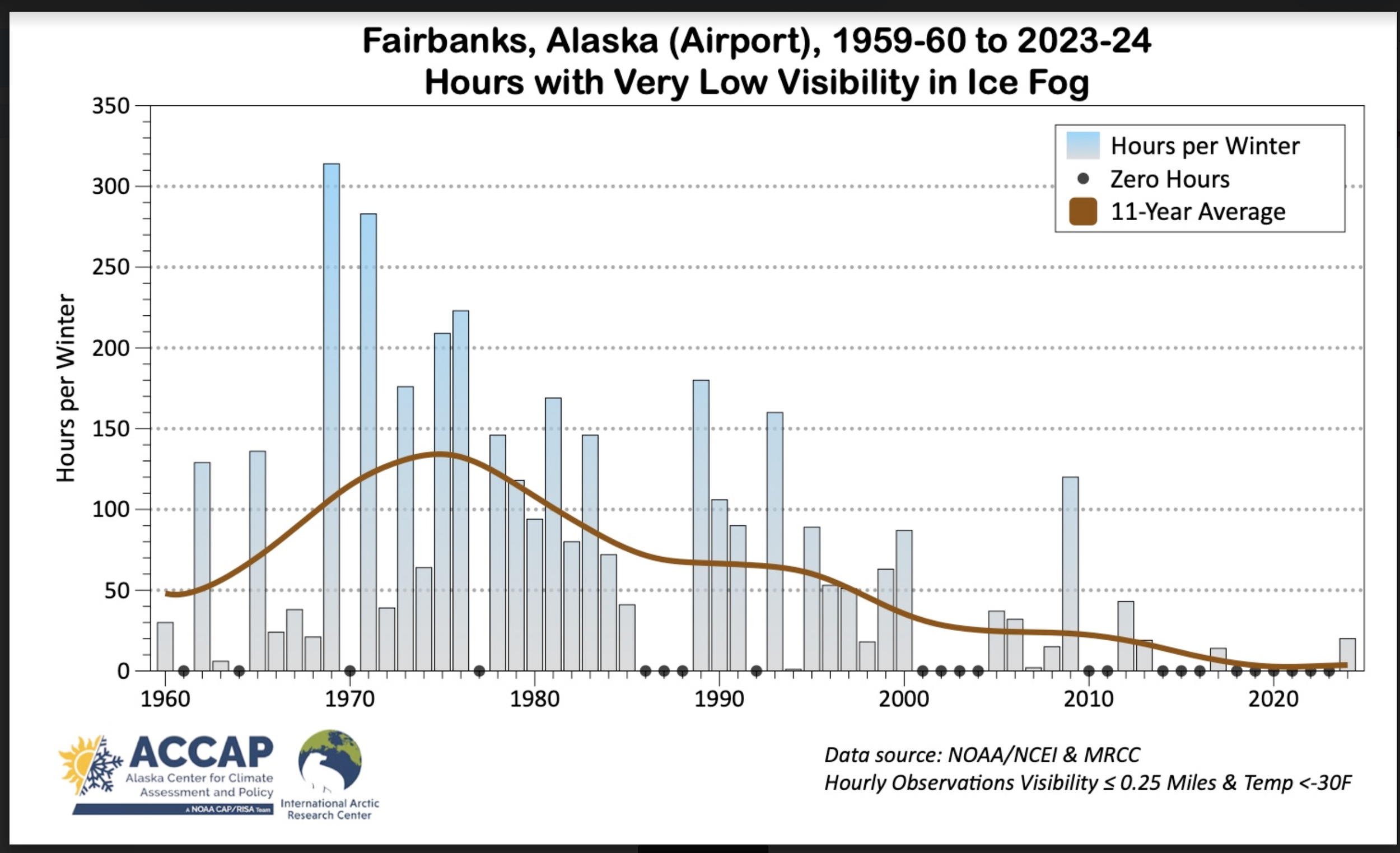

Meanwhile, scientist Rick Thoman reports that there was a 20-hour period at the airport of hourly observations with visibility of one-quarter mile or less, which is one way to define an ice fog incident.

“This breaks the run of winters with no dense ice fog (by this metric) but is barely a blip from the later 20th Century expectations,” he wrote.